Map courtesy of Todor Bozhidar

Thursday, 6th. September, 2012: the country celebrated the 127th. anniversary of Bulgarian Unification, according to the ‘new’ Gregorian calendar. Celebrations across the country, particularly in Plovdiv, commemorated the joining of the Principality of Bulgaria with Eastern Rumelia, as citizens enjoyed a traditional holiday in the closing days of an incredibly hot and dry summer.

But what exactly does this commemoration mean, in terms of Bulgarian history? To appreciate its true significance, one needs to refer to other ‘milestone’ events, both before and after 1885.

The painful but proud birth of a nation

Pre-1885

Bulgaria endured almost 500 years of ‘The Turkish Yoke’ as a territory occupied, subjugated and ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1396. April – May, 1876, saw the stirrings of revolt, as a subjugated people stirred up what was to become known as the April Uprising, a valiantly patriotic attempt to regain autonomy and sovereignty – an insurrection that rapidly developed into what became known as the Bulgarian National Revival.

The savage and brutal repression by the Ottoman Army and irregular Bashi-bazouks of these essentially guerrilla attacks provoked outrage in the west and the US. Britain and America despatched diplomats to investigate the emerging reports of massacres of Bulgarians (some 15,000 −30,000 in total, according to various estimates, including 5,000 slaughtered in the village of Batak alone).

April, 1877 – March, 1878: the Russo-Turkish War erupted, largely as a consequence of this emerging Bulgarian nationalism. Russia, of course, had other reasons for engaging with the Ottoman Empire, including re-establishing its influence in the Black Sea region and potentially regaining territory lost in the Crimean War, as well as reinforcing the religious force of Orthodoxy.

March 1878: the eventual victory of Russia and allied Balkan forces was recognised by the signing of the (Preliminary) Treaty of San Stefano, on 3rd. March,1878. Whereas Russia regarded this as a draft agreement, to facilitate a final and binding treaty agreed by the so-called Great Powers, it became the backbone of Bulgarian foreign policy until 1944, leading directly to the Second Balkan War and to Bulgaria’s disastrous involvement in WWI.

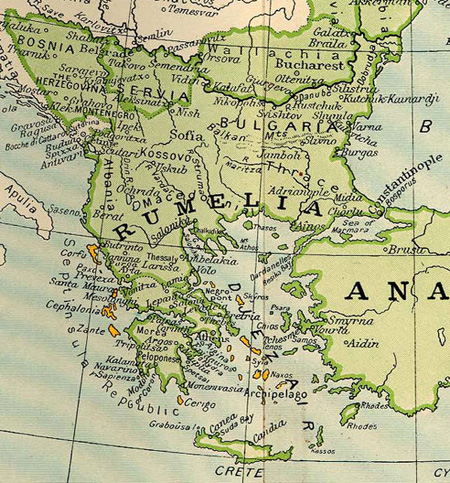

Meanwhile, however, the treaty legally set up “an autonomous self-governing tributary principality Bulgaria with a Christian government and the right to keep an army, though the state de facto functioned as independent nation. Its territory [see the map above] included the plain between the Danube and the Balkan mountain range (Stara Planina), the region of Sofia, Pirot and Vranje in the Morava valley, Northern Thrace, parts of Eastern Thrace and nearly all of Macedonia.”[Wikipedia]

June – July, 1878: San Stefano created a huge Bulgarian state, much to the alarm of Great Britain and the Austro-Hungarians. At the Congress of Berlin, also attended by leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Russia and the Ottoman Empire, the map was significantly redrawn.

Bulgaria, which was not represented at the Congress at the insistence of Russia, was chopped up into three parts: the Principality of Bulgaria, the autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia, and Macedonia, which was returned to the Ottoman Empire; thereby ending the dream of a russophile Greater Bulgaria whose access via the Aegean Sea to the Mediterranean so alarmed the western powers.

1885 – finally, unification

Bulgaria remained committed to reversing the dismantling of its newly-won territories and the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee (BSCRC), with the open support of the Bulgarian ruler, Knyaz Alexander I, successfully mounted a coup in the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia, unilaterally uniting them, despite active Russian opposition and passive promises of support (never fulfilled) from Britain.

Following months of press propaganda, and numerous demonstrations (even riots) demanding unification, the main action centred on the city of Plovdiv (then the capital of Eastern Rumelia).

A force of militia and armed unionists commandeered the Governor’s Residence on 6th. September. He put up no resistance. A temporary government was immediately set up, headed by Georgi Stranski. This new body sent a telegram to Alexander I, asking that he accept unification. Meantime, the local military was mobilised in anticipation of Ottoman ‘intervention’.

Alexander I replied within days and, as a proof of solidarity and acceptance, travelled to Plovdiv accompanied by the Bulgarian Prime Minister and the head of Parliament. Domestically, everything looked settled.

International reaction

Oddly enough, it took a few days for news of the event to reach the Ottoman Empire. They discovered that, legally, they could only enter Eastern Rumelia at the direct request of the Governor – who supported unification, and didn’t ask for assistance. They were also forcefully persuaded by Britain not to intervene.

For its part, Britain basically supported the Bulgarian move, although it was surprised to learn that Russia, because of its distrust of, and open conflict with, Alexander I, was not an active supporter of the coup. In fact, Russia removed its military from Eastern Rumelia, and suggested an international conference be set up to sanction what they viewed as a violation of the Treaty of Berlin. Both France and Germany supported this proposal.

Austro-Hungary, meanwhile, favoured Serbian expansion – but to the south and east, not to the north, where it could be threatened. Serbia itself also feared the influence of what was now the largest Balkan state, and was eying Macedonia.

Greece, similarly, was concerned at the size of the new state. It demanded territorial compensation and even declared war on Bulgaria, only to be restrained by Britain. However, Serbia went further and, promised Austro-Hungarian support, went to war on 14th. November, 1885, to be defeated within weeks by the Bulgarians.

A peace treaty, signed in Bucharest in February, 1886, acknowledged that there would be no change in the new borders, and went some way to establishing international acceptance of Bulgarian Unification.

The final move was the signing of the Tophane Agreement in April, 1886 – a treaty between the Ottoman Empire and the Principality of Bulgaria, and supported by the international powers. Alexander I was recognised as Prince of Bulgaria and Governor-General of the autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia. The issue of Bulgarian Unification was, therefore, settled, once and for all.

Post 1885

Unified Bulgaria remained eager to incorporate parts of Macedonia and the rest of Thrace.For example, the state supported the failed Ilinden-Preobrazhenia Uprising of 1903. A decade or so later, Bulgaria was embroiled in other, bigger wars, and the 1885 borders remain essentially the same to this day. (It’s necessary to modify even this statement – see Craiova and Dobruja, below).

Map of Rumelia, 1801

Historical and political curiosities

I promised previously that this would not be a history lesson – oh dear, even a basic description of the major events and players has proved so lengthy! Anyway, here are some of the smaller details I discovered while reading about this historical event.

Moesia

Historically, Moesia was an extensive area bounded to the south by the Balkan and Šar mountains, to the west by the River Drina, to the north by the Danube, and on the east by the Black Sea. The region was largely inhabited by the Thracians, Dacians, Illyrian and Thraco-Illyrian.

The name Moesia derives from the Moesi, a Thraco-Dacian people who lived there before the Roman conquest. Although the Romans subdued the populace as early as 75 BC, the area did not become a recognised Roman province until much later, towards the close of the reign of Emperor Augustus.

In 86 AD, following an attack by the Dacian king, Duras, the Romans reorganised the province, splitting it into Moesia Superior and Inferior. The former included what is now southern Serbia, while the latter extended to northern parts of Macedonia, northern Bulgaria, Dobrudja, southern Moldova and Budjak, an area of southwest Ukraine.

In terms of Bulgarian Unification, the Principality of Bulgaria was an integral part of ancient Moesia Inferior.

(Eastern) Rumelia

Rumelia, simply put, is the historic name for the Roman provinces of the Ottoman Empire that together form the Balkan Peninsula. The name Rûm means ‘Roman’ and Rumeli is ‘the lands of the Romans’.

Eastern Rumelia is thus a purely political invention, formulated by Britain during their meddling in Bulgarian and Balkan C19 affairs. There is no Western Rumelia, no Northern, no Southern!

As for Eastern Rumelia, the area included the present-day cities of of Plovdiv, Pazardzhik, Haskovo , Stara Zagora, Sliven, Yambol and Burgas.

The 1884 census records a total population of 975,000, with 70% being Bulgarians, just over 20% Turkish, and 5% Greeks. The 2001 census shows a population of almost 2.5 million, with 83% Bulgarians, 8% Turks, and only 0.1% Greeks.

The Tophane Agreement, April 1886

Named after a neighbourhood in Istanbul where it was signed, the Tophane Agreement between the Principality of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire Effectively recognised the fact of Bulgarian Unification 8 months earlier. In compensation, the Ottomans received territory in the region of Kardhzali and the Republic of Tamrash. Bulgaria managed to reclaim this land following its victory in the First Balkan War, 1912-13.

Republic of Tamrash, 1878-1886

Republic of Tamrash

Tamrash was a short-lived unilaterally-declared republic located on the southern borders of Eastern Rumelia. Inhabited largely by Pomaks who objected to the Christian principles of the emergent Bulgarian state and their Russian allies, this Rhodope autonomous region existed between 1878 and 1886. As noted above, it was transferred to the Ottoman Empire as part of the Tophane Agreement.

Bulgarian territories ceded to the Ottoman Empire, later regained

Dobrudja

Another small, but contentious region,situated around the mouth and delta of the Danube, shared historically by Romania (North) and Bulgaria (South). In ancient times a part of the Odrysian Empire, Dobrudja was eventually absorbed into the Roman province of Moesia.

The Dobrudja region, 1878

The San Stefano treaty awarded the territory, which had been under Ottoman rule since about 1420, to Bulgaria and Russia.

The Russians ceded the northern part to Romania in exchange for territory in Bessarabia. The southern part remained in Bulgarian hands, but was reduced in size by the Treaty of Berlin (at the insistence of the French, this time).

Bulgaria eventually regained the whole of southern Dobrudja in 1940, recognised by the Treaty of Craiova (below). This action was affirmed in the Paris Peace treaties of 1947. Further attempts to reorganise border territory continued until the early 60s, with no result.

Treaty of Craiova, September 1940

This treaty between the Kingdoms of Bulgaria and Romania saw the return of southern Dobrudja to Bulgaria. It was approved by all the great powers (who else!). As one of the terms of the treaty, some 80,000 Romanians were forced to move out of southern Dobrudja, with about 65,000 Bulgarians moved in the opposite direction.

Januarius A. MacGahan (1844-1878)

MacGahan was an American journalist who, at the instigation of the New York Herald and the British opposition paper, the London Daily News, was despatched to Bulgaria in 1876 to cover the atrocities reportedly being carried out by the Ottoman occupiers against the local populace, notably including the massacre of Batak.

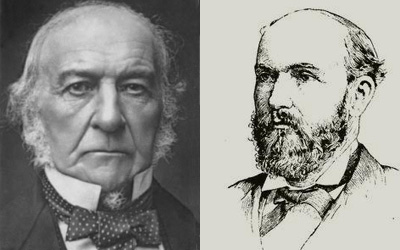

Gladstone (l.) and MacGahan (r.): champions of the Bulgarian cause

Directly spurred on by these reports, William Ewart Gladstone wrote and published his famous pamphlet “Bulgarian Horrors”, which in turn led to a complete change of British policy towards Turkey, until then a traditional British ally. This refusal to back the Ottomans against Russia, was a key factor, therefore, in the eventual formation of the modern Bulgarian state.

MacGahan died in Istanbul, aged 33. He was about to leave for Germany, to report on the imminent Conference of Berlin, when he was struck down with typhoid fever. He is still remembered throughout Bulgaria, with schools, streets and public squares named after him.

9th. September, 1944

If all this was not enough to digest over a protracted autumn holiday weekend, the 9th. September is also the occasion of yet another important commemoration of the turbulent history of Bulgaria.

The date records (I shan’t say ‘celebrates’) the 1944 events, as they remain divisive even today.

The Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria on 5th. September, to prevent it supporting and assisting Germany. The Red Army invaded on 8th. September, and a bloody overnight coup d’état, executed by Bulgarian communists without the need for the Red Army, effectively initiated a political system that endured until 1989.

This year, the opposition Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) marked the 68th. anniversary with events across Bulgaria. Right-wing parties instead commemorated the 8,000 named Bulgarian victims of the regime.

So, one way of looking at the 9th. September, is to view it as the date of the imposition of Communism in Bulgaria. The other is to regard it as an act of anti-fascist liberation. A neat balance.

Postscript

Excuse me for going on at such length above; but, apart from my own interest in learning more about the twists and turns of history and international vs. national politics, what became even more manifest to me in composing this, was the way a particular date in history always has its own raison d’être, and that this in turn provokes further significant events, sometimes far into the future. Plus, of course, we continue to witness what I call international meddling in other nation’s lives.

Only 10 days to go, until we celebrate Bulgarian Independence Day…

Sources: too many to quote, this time!

Image sources: treaty map: Todor Bozhinov; others: Wikipedia